Coastal erosion

Overview

- Ireland has a coastline of approximately 7400 km, comprising of extensive rock-dominated coasts along the southwestern, western and northern coasts and soft sediment dominated coast along the east and south east. The west coast is also characterised by major sedimentary areas in the form of large bays and estuaries.

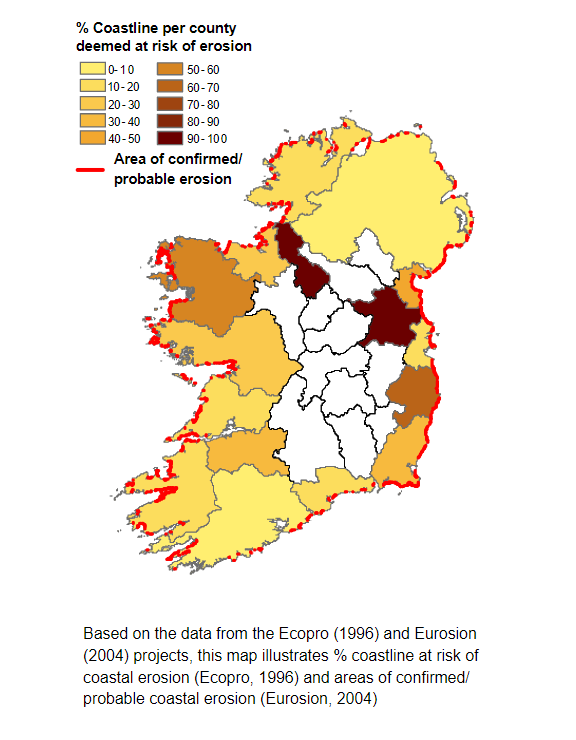

- Currently, approximately 20% of Ireland's coast is at risk of coastal erosion. The coasts most susceptible to coastal erosion are those composed of unconsolidated (soft) sediment. These areas are most common on Ireland's eastern and southern coasts and also in isolated areas, sedimentary bays, on western and northern coasts (e.g. the Shannon estuary, Donegal, Clew, Tralee and Dingle Bays).

- Projected changes in sea level in combination with projected increase in the severity of coastal storms is expected to exacerbate coastal erosion risk. It is thought that Ireland's coastal wetlands and soft sedimentary systems will be amongst the first in Europe to respond to storm-led sea level rise impacts.

- Coastal erosion currently represents a serious problem for Ireland and this is particularly the case where infrastructure or ecosystem services are at risk. Projected changes in sea level and in the occurrence of more intense coastal storms and surges mean that areas currently at risk will be at greater risk under projected changes in climate.

Current exposure

Coastal erosion is a natural phenomenon and is the process whereby the coastline is worn away by the sea through wave and storm actions and tidal currents.

Coastal erosion not only erodes sediments but also provides sediments to our coastal systems (e.g. beaches, dunes, reefs, mudflats and marshes) which provide a range of functions including absorption of wave energies, nesting and hatching fauna, protection of freshwater and location of recreational activities.

Levels of coastal erosion are determined by exposure to and the sensitivity of the coastline to coastal erosion. The coastline of Ireland is highly diverse with differing levels of exposure to erosion, and it is currently estimated that 25% of Ireland's coastline is subject to coastal erosion.

Increasingly, human influence (urbanisation and economic activities) in the coastal zone has turned coastal erosion from a natural phenomenon into a problem of increasing intensity.

Human-induced factors of particular concern are the construction of hard-coastal defences (e.g. seawalls, dykes, breakwaters, jetties) which aim to protect assets landward of the coastline. However, these constructions can exacerbate the problem of coastal erosion by impacting upon coastal processes.

Susceptibility of Ireland's coastline to coastal erosion

Ireland's coast is exposed to a high level of wave energy with breaking swells on Atlantic coasts reaching heights of up to 3m while on the east coast, wave heights are lower and between 0.5-2 m. The coasts most susceptible to coastal erosion are those composed of unconsolidated (soft) sediment and these areas are most common on Ireland's eastern and southern coasts and also in isolated areas, sedimentary bays, on western and northern coasts (e.g. the Shannon estuary, Donegal, Clew, Tralee and Dingle Bays).

Many of these soft coasts are low-lying, at less than 10-12 m above mean sea level and rates of erosion for these areas average 0.2-0.5 m per year but often reach values of 1-2 m per year. The effects of this erosion are visible as:

- "Rapid" cliff retreat;

- On-land movement of dunes and other barriers;

- And on beaches, the lowering of levels with the loss of finer sediments.

In contrast, for the rocky shores of the south and west, land loss can be as little as 0.01 m per century. Erosion episodes in these areas are generally characterised by sudden 'rock falls' or landslides.

Future exposure

Projected climatic changes will have a significant impact on rates of coastal erosion in Ireland. In combination, projected increases in relative sea level and in the intensity of coastal storms will have significant and lasting effects on coastal morphology. Changes in the occurrence of more intense coastal storms are projected to have a greater impact on rates of coastal erosion than relative sea level rise.

Projected changes in sea level and coastal storms

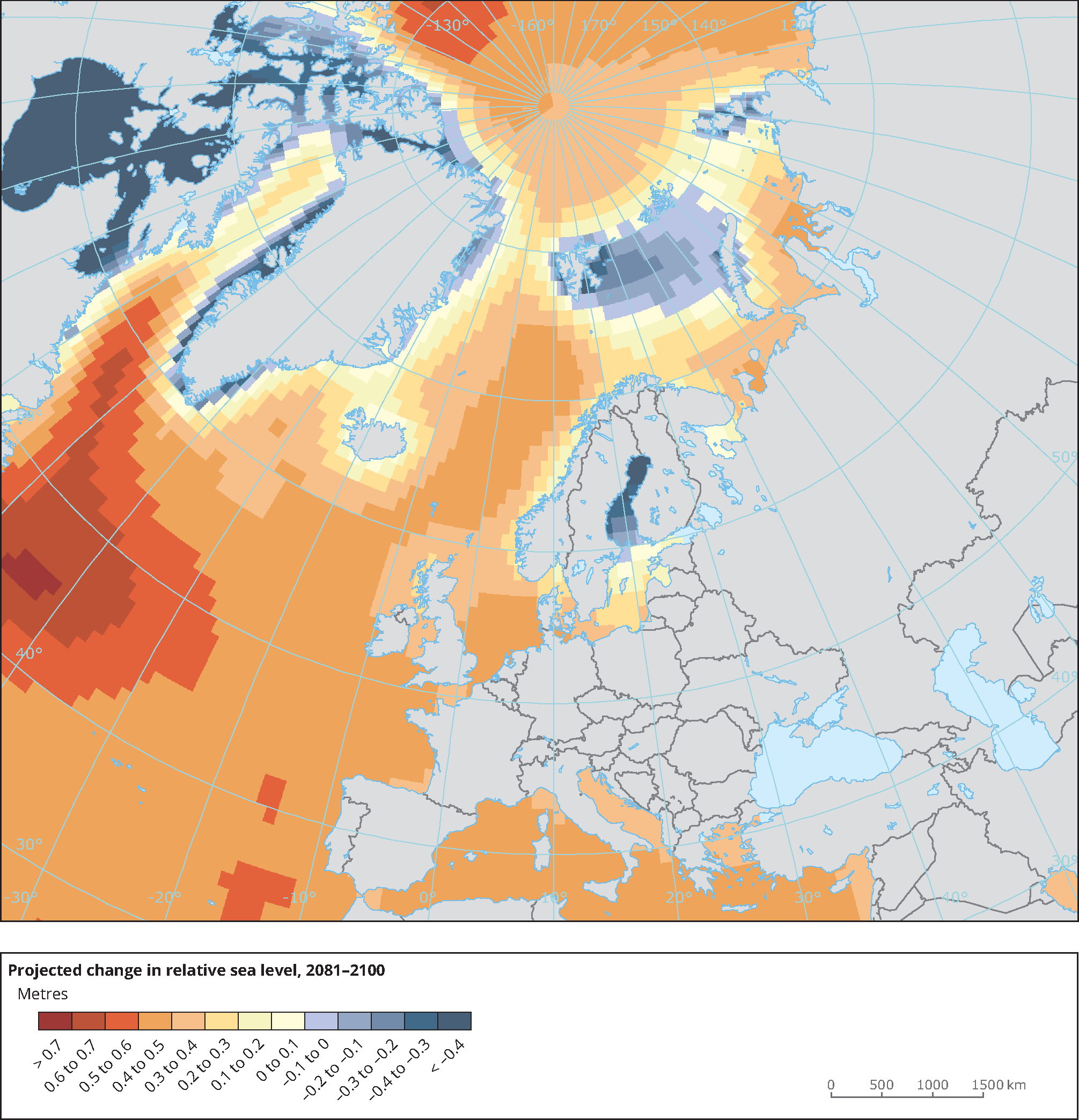

Findings of the IPCC project a rise in global mean sea level of 0.48m by the end of the century. Increasing sea levels will mean that the high tide line will move further up the shore and focus wave energy closer to the shore resulting in increased levels of coastal erosion. However, rates of increase will be spatially differentiated due to rates of land movements as a result of isostatic rebound. For example, the south of Ireland is sinking while the north of Ireland is still rising.

As demonstrated in the winter storms of 2013/2014, coastal storms have a significant impact on rates of coastal erosion. The number of intense coastal storms tracking over Ireland is projected to increase. These increase are expected to have a greater impact on rates of coastal erosion than those of sea level rise.

The map shows the projected change in relative sea level in 2081-2100 compared to 1986-2005 for the medium-low emission scenario RCP4.5 based on an ensemble of CMIP5 climate models. Projections consider land movement due to glacial isostatic adjustment but not land subsidence due to human activities [EEA, 2014].

Projected changes in levels of coastal erosion

Currently, c. 1700 km of the coastline is at particular risk of coastal erosion, and we can expect rates of erosion at these vulnerable locations to increase. However, it is very difficult to predict future changes in levels of coastal erosion as rates of increase will be determined by local coastal circumstances, e.g. geology, coastal configuration - exposure, sediments, supply factor, and land movement (isostatic rebound).

For Ireland, areas of the extreme southwest, from the Dingle Peninsula to Cape Clear, are likely to experience the largest increases at a rate of 3.3-4.8 mm per year while areas of the north east coast are likely to experience a rate of 2.2-3.7 mm per year. Therefore, areas of the south will likely feel the affects of projected climate changes first, particularly low-lying coastal locations situated on soft or easily eroded materials and coastal floodplains.

Implication for management

Coastal erosion currently represents a serious problem for Ireland, this is particularly the case in those locations where infrastructure or ecosystem services are at risk.

Projected changes in sea level and in the frequency of more intense coastal storms and surges mean that areas currently at risk will be at greater risk while those areas previously considered not at risk may be under threat.

Management in the short term

Measures need to be taken to develop understanding of coastal processes. This will form the basis for the implementation of subsequent measures.

In the short term, ensuring no new development is put at risk, developing an understanding of coastal processes and baseline information on those areas at risk of coastal erosion should form a priority. In addition, raising awareness and understanding of coastal erosion amongst all stakeholders should form an important part of your adaptation planning.

- Proposed developments in the coastal zone should be assessed in relation to current and future rates of coastal erosion;

- Coastal erosion is a cross government issue and requires a national approach. Collaboration between national, regional and local authorities is essential;

- Strengthen the knowledge base of coastal erosion and processes, and systematically identify and monitor areas currently at risk of coastal erosion;

- Monitoring should be included in any risk assessment or management studies, however baseline information must first be collected. Risk assessments should examine long term change, not just seasonal change, to ensure cyclical processes and offshore sediment budgets are considered prior to the installation of coastal defence structures.

Management for the medium to long term

In the medium to long term, it is essential to adopt a strategic approach which is based on a thorough understanding of coastal processes and which aims to accommodate natural and coastal sediment processes. Measures in the medium to long term can be categorised as:

- Hold the line: These measures aim to maintain the current position of the shoreline and consist of hard engineering solutions. A hold the line policy is generally expensive and normally applied to protect valuable infrastructure and/or assets. Examples of a hold the line policy can be seen in the Netherlands and is based on a thorough understanding of coastal processes.

- Retreat the line/managed realignment: This strategy allows for coastal recession but on a managed basis will generally rely on an engineering measures. However, due to losses of land property, this strategy can be contentious. In contrast to land loss, this strategy can have some benefits such as the creation of salt marsh areas and other tourist attractions.

- Advance the line: These measures aim to push the shoreline seaward and is generally achieved through land reclamation and beach re-nourishment projects.

- Do nothing: This involves allowing the coastline to evolve naturally and can be achieved through planning restrictions and set backs. For example, no development can take place within a fixed distance to the coastline, e.g. 100 m.